|

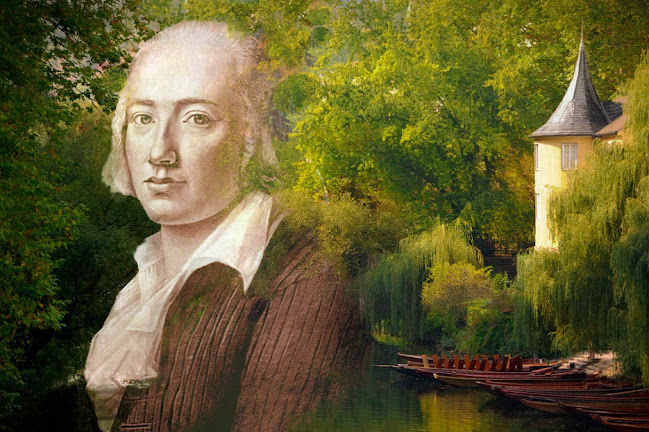

| 'Proclamation to the Shepherds', Heinrich Vogeler, 1902 |

In September 1900, the 27-year-old painter Heinrich Vogeler showed his friend Rainer Maria Rilke a sketch that depicted an angel announcing the birth of Jesus. Rilke, just 24 but already the author of several collections of verse, was struck by the image and made notes for some poems about the Nativity.

Eventually they took their place as three poems in Rilke's Das Marienleben (The Life of Mary), a sequence published in 1913. It celebrates the human side of the Christmas story, describing Mary and Joseph's struggle to understand what was happening to them. In translating 'The Birth of Christ', I've tried to reproduce Rilke's plain-spoken but thoroughly wonderstruck language.

THE BIRTH OF CHRIST

Without your simplicity, how could this

have happened--what now shines in the dark of night?

The God who thundered over the nations

makes himself mild and through you enters the world.

Were you expecting something greater?

What is greatness? He moves straight through

all measurements we know, dissolving them away.

Even the path of a star is not like that.

Behold: these kings standing here are great

and drag into your lap rare treasures

that each believes to be the greatest.

Perhaps you are astonished at their gifts.

But look into the blanket in your arms,

how He already surpasses all of them.

Amber that is traded near and far,

rings of gold and costly spices

that drift for a moment on the air:

these are quickly fading pleasures

and leave behind a vague regret.

The gift He brings--as you will see--is joy.

'Geburt Christi' (The Birth of Christ), Rainer Maria Rilke

In a 1913 letter to the Czech writer Hugo Salus, Rilke said of Das Marienleben, 'It is a little book that was presented to me, quite above and beyond myself, by a peaceful generous spirit, and I shall always get on well with it, just as I did when I was writing it.' (Translation by H.D. Herter Norton.)

In a 1913 letter to the Czech writer Hugo Salus, Rilke said of Das Marienleben, 'It is a little book that was presented to me, quite above and beyond myself, by a peaceful generous spirit, and I shall always get on well with it, just as I did when I was writing it.' (Translation by H.D. Herter Norton.)