You

too sought greater things, but the weight of love pulls

All of us down, and grief drives us even

lower.

Yet the arc of our lives back

Where they came from is not in

vain.

High

or low! Does a hand not rule silent Nature

In holy night where all the days to come are planned,

In holy night where all the days to come are planned,

And even Hell’s fractured maze--

Ruled by degree, and judged by law?

This much I have learned: unlike mortal masters, you

Heavenly, all-sustaining powers have never

Led

me, as far as I know,

Along any level pathway.

A

person tries all that life brings, say the heavens,

So that, well nourished, we may give thanks for it all

And understand the freedom

To set forth wherever we wish.

“Lebenslauf,”

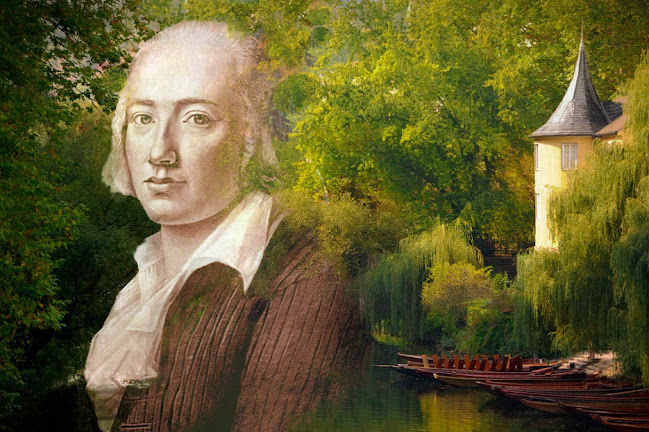

Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843)

Summer 1800

Translated by Frank Beck 2018

Many poets revise their poems after their initial publication. Usually the purpose is to bring the poem closer to the writer's original intent. With "Lebenslauf," Friedrich Hölderlin did something unusual: he took a poem about sorrow written two years earlier and rewrote it as a longer poem that expresses a nearly opposite point-of-view.

The original four-line poem was one of 17 short poems Hölderlin sent to his friend, Christian Ludwig Neuffer, in the summer of 1798 for use in an anthology called A Pocket Book for Educated Ladies. At the time, Hölderlin was a 28-year-old former seminary student working as a private tutor for the Gontard family in Frankfurt. He had fallen in love with his student's mother, Susette Gontard, and the relationship had grown tense. The poem, however, expresses not anguish but resignation:

High was my spirit's aim, but love has already

Drawn it lower, and grief weighs it down even more.

So I am making my way

Through life's arc, back to where I began.

The two years between that poem and the longer one were pivotal ones in Hölderlin's life. He left the Gontard household and moved to nearby Homburg, remaining in touch with Susette. In 1799 he published the second volume of his epistolary novel, Hyperion, set against the backdrop of Greece's fight for independence.

Paradoxically, the suffering caused by parting with Susette made Hölderlin less self-centered. His previous poetry had emphasized life's tragedies; now he wrote with greater freedom, often in a prophetic vein. Rather than lamenting the problems of his existence, he celebrated what he thought life could be, in its highest and most satisfying form.

During those two years, as Michael Hamburger has shown, Hölderlin learned from the Greeks how to make his poetry more sensuous and concrete. In the case of "Lebenslauf", the quiet resignation of the earlier poem gave way to an heroic self-assertion that seeks to speak for his readers, as well as for himself.

During the following seven years, Hölderlin wrote "Bread and Wine" and the other extended poems for which he is best known. In 1807, however, he suffered a severe mental collapse. He spent the remaining 36 years living in seclusion, cared for by the family of Ernst Zimmer, a poetry-loving carpenter in Tübingen, a town near Stuttgart.

Summer 1800

Translated by Frank Beck 2018

Many poets revise their poems after their initial publication. Usually the purpose is to bring the poem closer to the writer's original intent. With "Lebenslauf," Friedrich Hölderlin did something unusual: he took a poem about sorrow written two years earlier and rewrote it as a longer poem that expresses a nearly opposite point-of-view.

The original four-line poem was one of 17 short poems Hölderlin sent to his friend, Christian Ludwig Neuffer, in the summer of 1798 for use in an anthology called A Pocket Book for Educated Ladies. At the time, Hölderlin was a 28-year-old former seminary student working as a private tutor for the Gontard family in Frankfurt. He had fallen in love with his student's mother, Susette Gontard, and the relationship had grown tense. The poem, however, expresses not anguish but resignation:

High was my spirit's aim, but love has already

Drawn it lower, and grief weighs it down even more.

So I am making my way

Through life's arc, back to where I began.

The two years between that poem and the longer one were pivotal ones in Hölderlin's life. He left the Gontard household and moved to nearby Homburg, remaining in touch with Susette. In 1799 he published the second volume of his epistolary novel, Hyperion, set against the backdrop of Greece's fight for independence.

Paradoxically, the suffering caused by parting with Susette made Hölderlin less self-centered. His previous poetry had emphasized life's tragedies; now he wrote with greater freedom, often in a prophetic vein. Rather than lamenting the problems of his existence, he celebrated what he thought life could be, in its highest and most satisfying form.

During those two years, as Michael Hamburger has shown, Hölderlin learned from the Greeks how to make his poetry more sensuous and concrete. In the case of "Lebenslauf", the quiet resignation of the earlier poem gave way to an heroic self-assertion that seeks to speak for his readers, as well as for himself.

During the following seven years, Hölderlin wrote "Bread and Wine" and the other extended poems for which he is best known. In 1807, however, he suffered a severe mental collapse. He spent the remaining 36 years living in seclusion, cared for by the family of Ernst Zimmer, a poetry-loving carpenter in Tübingen, a town near Stuttgart.

For nearly a century, Hölderlin's work was not widely known, but in 1913 a young German scholar named Norbert von Hellingrath began publishing an edition of his poems that eventually filled six volumes. Rainer Maria Rilke saw some of the manuscripts while the edition was being prepared, and they became an important influence on the Duino Elegies, which Rilke published in 1923.

|

| The first two stanzas of the 1800 poem in Hölderlin's hand (Württembergische Landesbibliothek) |